|

| Source: Vox.com |

Britain in 1945.

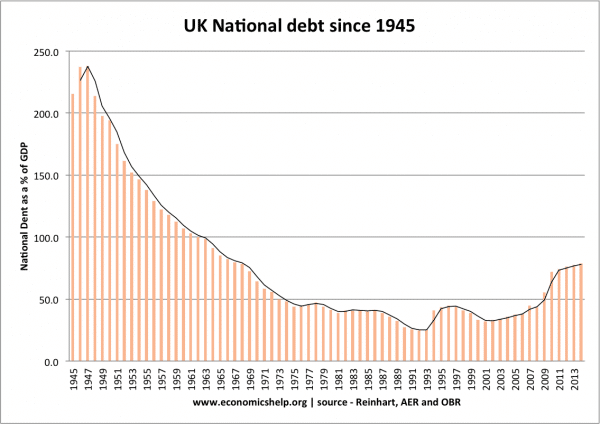

In 1945, Britain was triumphant in defeating the axis powers. It appeared to be one of the Big Three powers. But, the reality was - it were completely broke. The war had exhausted its financial reserves. It is fashionable to worry about the UK national debt (currently 60% of GDP). But, in the 1940s, this had reached over 200% of GDP.

This scale of debt, was the over-riding feature of our post war economy which hung like a shadow over the UK economy and UK politics.

In 1946, towards the end of his life, it sent the great economist - Lord Keynes to Washington to help argue for an £8bn loan. People say that despite his ailing health, this was one of Keynes' greatest hours - passionately and brilliantly explaining why Britain needed a loan. The American's politely listened - only to refuse.

It was only the heightening of cold war tensions that America became motivated to bailout Britain and the rest of Europe. But, whatever the motive, it is certain the America loans were vital to keep the UK economy afloat - especially in that awful winter of Britain in 1947, where secret government records show they drew up contingency plans for mass starvation.

(Source: http://econ.economicshelp.org/)

Year 1947, Cold War

US supports the anti-communist side in the Greek Civil War,

extending military and financial aid to the countries of Western Europe

Creates NATO.

(The Berlin Blockade (1948–49) was the first major crisis of the Cold War. In 1949 UK helped US form NATO as a military alliance against the Soviet Union. UK fought North Korea and China in the Korean War from 1950 to 1953)

Year 1957 - European Economic Community (EEC) is created by the Treaty of Rome

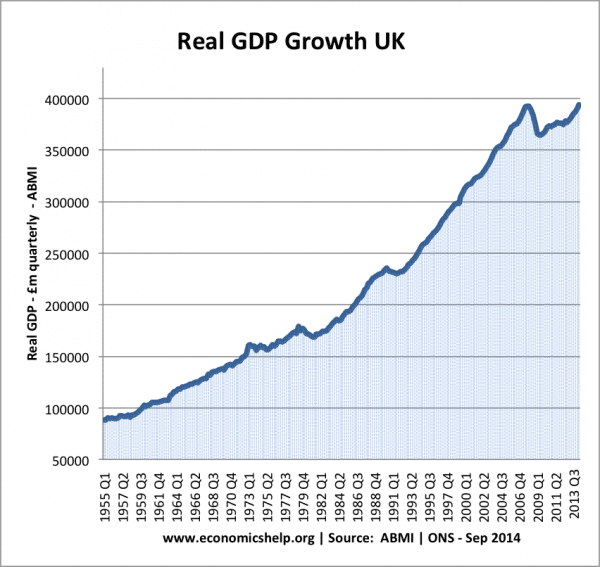

The 1940s and 1950s, were an age of austerity (rationing only ended in 1954) for Britain. But, it was an era of full employment. And after the horrors of the Great Depression, this was no small thing. With the end of rationing, and the booming of global trade, living standards rose rapidly. We entered a new era of consumption - labour saving devices like vacuums and washing machines became the norm rather than the exception. In 1957, Harold Macmillan proclaimed in a speech that 'people have never had it so good' - A sentiment that seemed to express the improvement in living standards of the 50s and early 60s. Yet, despite the improvements in living standards. Britain was quietly slipping behind our competitors. And this period of prosperity would soon be challenged.

(Source: http://econ.economicshelp.org/)

Why did UK debt to GDP fall?

- Economic growth averaging 2.5% +. Total real debt increased in this period, but GDP increased at a faster rate. Therefore, the debt to GDP ratio fell.

- Positive inflation.

- Patience. After early 1950s, debt to GDP fell over the next four decades. It took a long time to reduce debt to GDP.

- Relatively low budget deficits (though the UK very rarely had a budget surplus)

(http://www.economicshelp.org/blog/)

Year 1961

Britain: I wish to apply to join EEC.

The cries of “shame” stabbing through the cheers when the Prime Minister announced that we are making formal application to join the European Economic Community came from both sides. So did the portentously eager applause when he insisted that we shall not take the final step unless our Commonwealth and other obligations can be reconciled, for otherwise the “loss would be greater than the gain.”

15 January 1963: President De Gaulle lays down impossible conditions for British entry to the EEC

1 January 1973: Britain joins the EEC

Why does the European Union exist, anyway?

Europe is a collection of countries that used to fight a lot. For example, in World War II countries within Europe fought against one another, and it greatly hurt the continent.

So after WWII, many countries felt it was important to integrate European countries — starting with the coal and steel industries and then expanding to a broader set of trade issues.

Countries often make rules about things coming into their countries. For example, if you wanted to make a car in France and ship it to Britain, you would have to pay a tariff to Britain to do so.

Western Europe has dozens of countries, each with its own trade, immigration, and economic policies. Trying to navigate these rules was very inefficient. The European Union essentially started from a question: What if each country had the same rules? What if all the barriers came down?

And that’s what the EU did.

There are challenges to cooperation. When something bad happens, it affects everyone.

The appealing part of the EU was that it made it easier for European countries to share in one another’s prosperity. But, as with any union, cooperation means weathering downturns together — and that hasn’t always been so easy.

Take, for example, the 2008 financial crisis. Many economists agree that the European Central Bank failed to respond effectively, leading to a recession that was much more severe than it needed to be. Unemployment rose, and tax revenue fell. Banks needed bailouts, and debt in a number of EU countries soared.

Seeing the EU in such crisis made some have second thoughts about being yoked to it — and increased worry among wealthy countries (like the UK) that they might have to help bail out less wealthy countries down the line.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6702803/6.png) |

| http://www.vox.com/2016/6/24/12025514/brexit-cartoon |

Tensions over immigration have risen significantly in Britain in recent years

Twenty years ago, barely anyone thought immigration or race relations was one of the country’s most important issues.

Times have changed.

In a survey conducted last year, 45 percent of Brits identified "immigration/race relations" as a top issue facing the country.

Last year, British Prime Minister David Cameron announced a referendum on whether Britain should remain in the European Union.

That’s Brexit, the vote that happened yesterday.

And by a slim margin, the British voted to leave the European Union.

Untangling from the EU would be a long, painful process

The UK and the EU have two years to figure out the terms of the exit — what rules would still apply to Britain and what privileges Britain would still get.

If there isn't some kind of deal that softens the blow — that lets Britain continue to take advantage of at least some of the European Union cooperations the country previously enjoyed — it'll be ugly.

what next ?

Britain’s prime minister has resigned,

sterling has had one of its biggest one-day falls in history (around 11%)

Scotland has opened the process of calling a second independence referendum.

Even the Leave campaigners are balking at invoking Article 50 immediately;

Article 50 says:

“Any member state may decide to withdraw from the union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements.”

The article is a provision that gives negotiators two years from the date of article 50 notification to conclude new arrangements. Failure to do so results in the exiting state falling out of the EU with no new provisions in place, unless every one of the remaining EU states agrees to extend the negotiations.

In his resignation speech, David Cameron made it clear he was in no hurry to push the button. “A negotiation with the European Union will need to begin under a new prime minister and I think it is right that this new prime minister take the decision about when to trigger article 50 and start the formal and legal process of leaving the EU,” he said.

That means it won’t be until October.

The nature of Britain’s trading relationship with the EU will not become clear until late 2018 at the earliest. All the more reason, then, for investors and businesses to delay any decision to put money into Britain; the potential economic damage is greater.

The problem for Britain is that it has a huge current account deficit, which needs financing from abroad. There is much talk about the way that a weaker sterling can boost exports, but it also raises the costs of imports (like oil) which will widen the deficit in the short term.

A weaker pound will also lead to higher inflation. Two things can happen in response. Either wages can rise in compensation, in which case business costs will rise and the competitive advantage of devaluation will be eroded. Or wages won’t rise and people's living standards will be eroded. So a Leave campaign fuelled by voter anger over squeezed living standards will result in a further squeeze in those living standards.

(http://www.economist.com/blogs/buttonwood/2016/06/after-referendum)

No comments:

Post a Comment